Rhode Island Poised to Make History It Doesn’t Want to Make

March 5, 2021 · 12:57 PM EST

Rhode Island may be America’s tiniest state, but it’s on the verge of making political history in 2022.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, you would be hard pressed to find anyone in the state who thinks that’s a good thing.

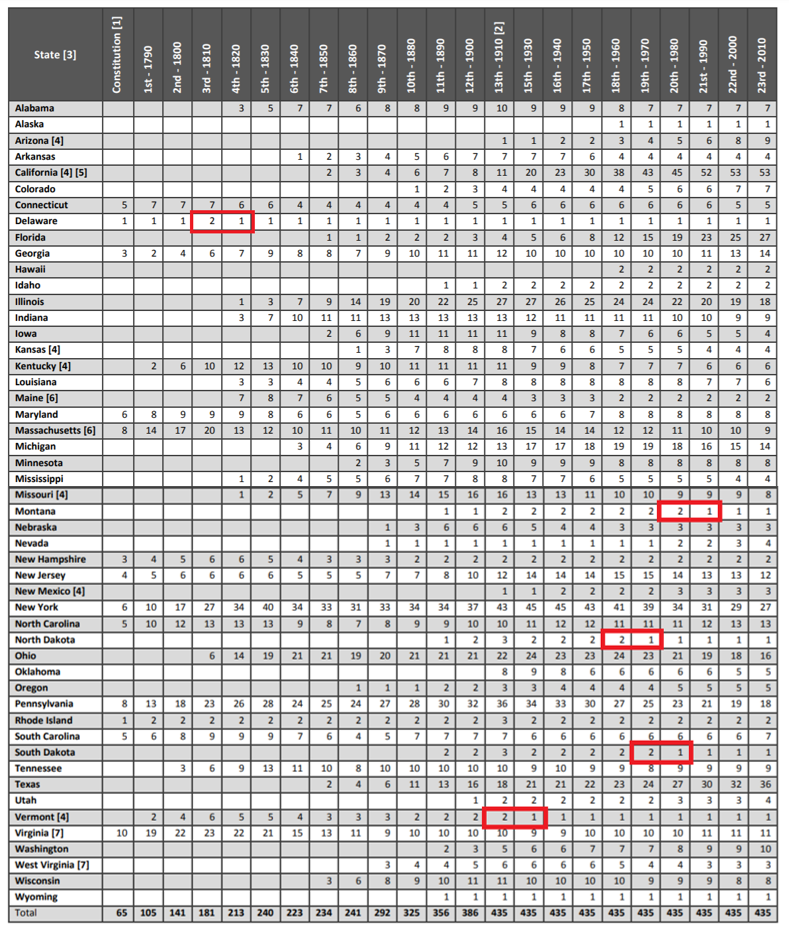

According to estimates from Election Data Services, a political analytics firm, Rhode Island is likely to be one of 10 states that will lose a congressional seat as a result of the 2020 census and subsequent reapportionment process. For the Ocean State, that means going from two seats in the U.S. House to just one, elected by the state at-large. It will be the first time since 1792 that Rhode Island has sent only one House representative to Washington, DC.

Rhode Island will join Delaware, Vermont, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana in the pantheon of states that went from having multiple districts to one at-large representative. It’s an ignominious achievement, generally accompanied by a loss in congressional clout.

It also means a significant decrease in the relative representation of any individual Rhode Islander. Currently, the state’s two congressional districts are the least populated of any in the country; so the resident-to-representative ratio is a national-best 528,562-to-1. In an at-large district, that ratio would be national-worst 1,057,125 residents to one representative.

But Rhode Island’s situation may be distinct from the five states that came before it, because both of Rhode Island’s members of Congress — Jim Langevin and David Cicilline — are from the same party, and both look likely to run for the at-large seat in 2022, setting up a clash in the Democratic primary.

That has never happened before.

In all previous instances of a state moving from multiple members to a single representative, the two incumbents were either from different parties, or one chose to step aside rather than seek re-election against their colleague.

Delaware had two congressional districts from 1812 to 1822, but lost one of them following the 1820 census. At the time of the 1822 election for the single at-large representative, only one of the state’s two seats was occupied, by Federalist Rep. Louis McClane. Democratic-Republican Rep. Caesar Augustus Rodney had been elected to the Senate earlier that year, leaving the soon-to-be eliminated second seat vacant. (A cousin, Federalist Daniel Rodney, won a special election to complete Rep. Rodney’s term, but did not run in the concurrent general election for the remaining seat.)

Following the 1932 census, Vermont was reapportioned down from two seats to one. At the time, the state had two Republican representatives: John Eliakim Weeks and Ernest Gibson. Weeks, who had previously made history as the first man to be elected to a second two-year term as governor, chose to retire rather than run against Gibson. Interestingly, Gibson, who had previously represented only the eastern side of the state, still faced a primary challenge for the at-large seat, from state Sen. Loren Pierce. Gibson won, 70-30 percent.

North Dakota lost its second seat after the 1970 Census. The state had been represented by Democratic-NPL Rep. Arthur Link and Republican Mark Andrews, but following reapportionment Link ran for the open governorship instead, winning by a narrow 51-49 percent, while Andrews, who had previously represented only the eastern part of the state, cruised to a 73-27 percent victory in the at-large district.

The first time reapportionment actually forced two sitting members of Congress to compete for an at-large district was in 1982, in South Dakota. Future Democratic Senate Majority Leader/then-Rep. Tom Daschle, who had won his 1978 congressional race in the state’s eastern district by just 139 votes, faced off against freshman Republican Clint Roberts, who had represented the western part of the state, winning by a tight 52-48 percent.

Ten years later, it would be Montana’s turn to face the political Grim Reaper, with a similar result to South Dakota. Democratic Rep. Pat Williams and Republican Rep. Ron Marlenee served together in the House for 14 years, but that didn’t stop the two from battling it out for Montana’s new at-large district in 1992. Williams, who had represented the traditionally Democratic western part of the state, won that fight 50-47 percent. (Thirty years later, Montana is likely to gain a second seat in this round of reapportionment.)

Over the last 232 years, America has played host to tens of thousands of congressional elections. But it has never seen two incumbents face off in a primary for an at-large district. Come 2022, that’s something only Rhode Islanders may be able to say. But for some reason, Democrats in the state just don’t want to talk about it.

Subscribers can read a deep dive into a potential 2022 Democratic primary for Rhode Island’s At-Large district in this week’s newsletter.