Senate Candidates Smashing the Fundraising Curve

July 29, 2021 · 2:00 PM EDT

When fundraising reports trickle out quarter by quarter, it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture: candidate fundraising over the last couple cycles has soared.

In 2014, Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes and Republican Mitch McConnell raised a combined $49.8 million in their battle for one of Kentucky’s Senate seats. It was the most expensive race that cycle. But a combined fundraising haul of nearly $50 million would not have even cracked the top 10 most expensive Senate races of the 2020 cycle. It would have ranked 13th, right between #12 Texas ($64 million) and #14 Alabama ($40.7 million).

Running for the U.S. Senate has been an expensive proposition for years. Waging a statewide campaign, often across several media markets, takes serious resources.

But over the past decade, Senate races have gone from being merely expensive to being a multi-billion dollar nationwide melee.

A review of Federal Election Commission filings from the past six Senate cycles reveals an accelerating financial arms race that has transformed politics in states from Alaska to Florida and everywhere in between.

All figures cited come from the final round of FEC filings in each cycle, and reflect the total amount of money raised by each party’s nominee over the course of the election, including money a nominee donated or loaned to their own campaign. It includes fundraising during the primary and the general elections, but does not include fundraising by candidates who did not win their party’s nomination.

This analysis does not include spending by the party campaign committees or outside groups such as Super PACs and 501(c)4 organizations.

The Big Picture

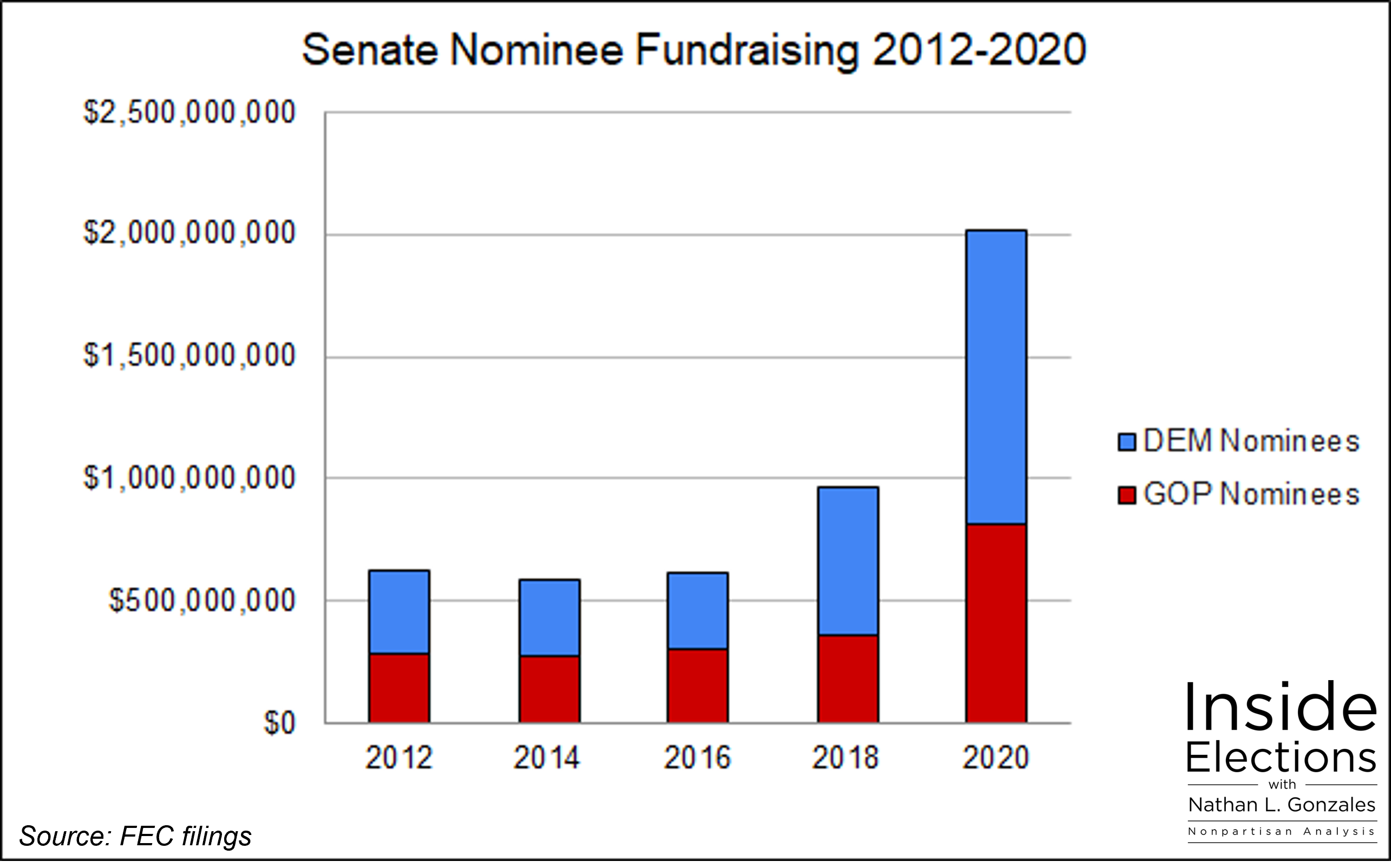

In 2012, Democratic and Republican nominees in Senate races across the country raised a combined $628 million, an average of $9.5 million per nominee.

Just eight years later, in 2020, Senate nominees raised an astounding $2.08 billion, with the average nominee pulling in $28.8 million. Even excluding 2020’s costly special elections in Georgia and Arizona, the cycle weighed in at a hefty $1.6 billion, an average of $24.6 million per nominee.

This massive escalation only began in the latter half of the decade. In fact, the first three Senate cycles of the 2010s — in 2012, 2014, and 2016 — all saw Democratic and Republican nominees combine for roughly the same amount, around $600 million. It was not until 2018 that nominees started raising appreciably more money ($965 million that year), setting a new record that would be eclipsed soon after by 2020’s nominees.

As the graph below shows, however, the spending surge was not equal among both parties.

While Democratic nominees have outraised their GOP counterparts in every cycle since 2012, the party’s advantage was initially small: $53.4 million in 2012, $38.6 million in 2014, and $5.8 million in 2016.

But 2018’s set of Democratic nominees nearly doubled the mark set by 2016’s Democrats ($309 million) by raising a collective $609.2 million, while their GOP counterparts only modestly improved on Republicans’ 2016 haul ($303 million), raising $355.6 million.

So after three election cycles of relative spending parity, Democrats enjoyed a $253.6 million advantage over Republicans in 2018 — an advantage that did not stop them from suffering a net loss of two Senate seats.

In 2020, Republicans successfully kicked their Senate fundraising into high gear, with their nominees raising $810 million, more than twice 2018’s nominees. But Democrats kept pace, nearly doubling their 2018 mark as well, pulling in $1.2 billion and extending their financial advantage over the GOP nominees to $398 million.

Apples to Apples

The growth in fundraising every two years is striking. But because the Senate operates using six-year terms, the composition of seats up for grabs is different from year to year, and only repeats every third cycle when the initial “class” of Senate seats comes back up for election.

In 2012, the most expensive Senate race in America was in Massachusetts, where Republican Scott Brown faced a spirited challenge from Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Warren. Combined, Brown and Warren raised nearly $71 million over the course of their campaigns.

Six years later, when the same class of senators faced voters again, the most expensive race of the bunch was in Texas, where Republican Ted Cruz fended off Democrat Beto O’Rourke. That slugfest saw the two candidates raise a combined $126 million, setting the fundraising pace for the field at nearly twice that of 2012.

In aggregate, Senate nominees in 2018 raised $962 million, 1.5 times as much money as Senate nominees in 2012 ($628 million).

Again, the increase was more apparent among Democrats than Republicans. Democratic nominees in 26 of the cycle’s 33 Senate contests outraised their 2012 counterparts, while just 16 GOP nominees outraised the previous GOP nominee in their respective race. The average Democratic haul jumped from $10.3 million to $18.5 million, while the average GOP haul increased from $8.7 million to $10.7 million.

The uptick between 2014 and 2020, the last two cycles in which Class II Senate seats were on the ballot, is even more dramatic. In 2014, Senate nominees raised a combined $589 million, while in 2020 they pulled in an astounding $2.02 billion, or 3.4 times as much.

In 25 of the 33 regularly scheduled races (not including special elections in Arizona and Georgia), the Democratic nominee outraised their 2014 counterpart, and the average haul leapt from $9.2 million to $34.5 million. In those same 33 races, 18 of 33 GOP nominees outraised their 2014 counterpart, with the average GOP haul increasing from $8.1 million to $23.1 million.

As in 2014, Kentucky’s two nominees — McConnell and Democrat Amy McGrath — put on fundraising masterclasses and pulled in a combined $170 million, or 3.4 times as much as the pace-setting 2014 total. But in a sign of how much more expensive 2020 was than 2014, that $170 million total only made Kentucky’s contest the fifth-priciest of the cycle, when looking at candidate money.

The top spot went to Georgia’s regularly scheduled election, which pit Sen. David Perdue against Democrat Jon Ossoff; the two raised a combined $259 million. Because that race went to a Jan. 5, 2021 runoff, both nominees had an extra two months — and the Senate majority hanging in the balance — to boost their fundraising numbers. But in second place was South Carolina, where Democrat Jaime Harrison smashed quarterly fundraising records en route to a $132 million total haul, and Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham raised $112 million, more than any GOP Senate candidate in history.

Expectations for 2022

The shifts between 2012 and 2018, and 2014 and 2020, represent a dramatic escalation in the financial arms race surrounding the battle for the Senate, one that looks likely to continue heading into the 2022 midterms.

The seats up for grabs in 2022 were last on the ballot in 2016. That year, nominees combined to raise $586 million, roughly in line with the $589 million raised by 2014’s nominees and the $628 million raised by 2012’s nominees. And Democratic donors hadn’t yet been awakened by Trump’s victory and presidency.

But already, with 15 months still to go before Election Day, the 2022 field is acting more like 2018 and 2020 and less like 2012, 2014, and 2016. In Florida, GOP Sen. Marco Rubio has already raised $11.5 million through June 30, equal to nearly half of his entire haul in the 2016 cycle. His likely Democratic opponent, Rep. Val Demings, raised $5 million through the end of June, a little more than a quarter of what Rubio’s 2016 opponent Patrick Murphy raised over the entire cycle.

Demings isn’t the only challenger showing some early financial muscle. Democratic Lt. Gov. John Fetterman has already raised $6.5 million for his campaign in Pennsylvania. In 2016, Democratic nominee Katie McGinty raised just $18.5 million over the course of the entire election cycle.

In New Hampshire, incumbent Democrat Maggie Hassan may find herself in a highly competitive race against GOP Gov. Chris Sununu. The senator has already raised $11.3 million, more than half her total haul in 2016 ($18 million) when she won the closest Senate race in the country. It’s a similar story in Nevada, where Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto has already pulled in $11.6 million after raising just $20 million total to win a competitive open seat race in 2016.

The escalation extends to less competitive races as well. In 2016, Tammy Duckworth was one of Democrats’ bright spots on a bad night when she defeated GOP Sen. Mark Kirk in Illinois. She raised $16.4 million for that race, and has already pulled in $8.4 million this cycle despite not being particularly vulnerable. Next door in Indiana, Republican Todd Young raised $10.7 million in his successful 2016 fight against former Sen. Evan Bayh, a Democratic heavyweight. In 2022, Young doesn’t look at risk, but he’s still already raised $7.5 million.

The ability to build a national fundraising network has become a major asset for Senate hopefuls, and a key consideration for parties looking to maximize their gains in the upper chamber.

In Florida, Democratic Rep. Stephanie Murphy spent three months laying the groundwork for a run against Rubio. As a moderate, Spanish-speaking former refugee whose family escaped from communist Vietnam, Murphy brought a lot to the table as a potential candidate. But Democrats in DC had their eyes on another member of the Florida delegation: Demings, the former Orlando police chief.

It wasn’t that Democrats disliked Murphy, or so they insisted. But rather, strategists in Florida and DC felt that Demings’ national profile as a longtime police officer, former impeachment manager and a reported Biden vice presidential shortlister — her potential to make history as only the third Black woman elected to the US Senate — would help her raise the massive amounts of grassroots money needed to compete in an expensive state against a well-funded opponent.

When Demings made her decision to run for Senate, rather than for governor, as some expected, Murphy quickly saw the writing on the wall and pulled the plug on her all-but-announced campaign, and is instead running for re-election to the House.

And in Pennsylvania, Fetterman’s transformation from 2016 insurgent to 2022 national fundraising juggernaut has the DSCC more content to stay on the sidelines in the primary (at least for the moment), a departure from six years ago when DC Democrats intervened to push McGinty over the finish line.

The Bottom Line

The Trump presidency drew unprecedented attention to Senate races across the country, attention that manifested not just in record fundraising but also the highest rates of voter turnout in a century.

With Trump out of the White House and not appearing on the ballot, the fundamental question of the 2022 midterm elections is if the trends of the last four years will persist or revert to the pre-2016 norm.

We won’t have a definitive answer on turnout for more than a year.. But when it comes to Senate fundraising, even at this early stage the 2022 cycle looks more in line with 2018 and 2020 than it does to 2016 or the rest of the pre-Trump era.