Fewer Political Ads Now, Doesn’t Mean Less Advertising Later

April 15, 2020 · 10:00 AM EDT

The coronavirus has put a temporary end to simple things such as sitting at a restaurant or going to a baseball game, but don’t declare the end of political advertising just yet.

With travel, rallies, and in-person campaigning severely curtailed, and campaigns striving to maximize communication channels that they can control, paid advertising in general, and television advertising in particular, will likely be the best vehicle for campaigns to deliver the messages they want delivered.

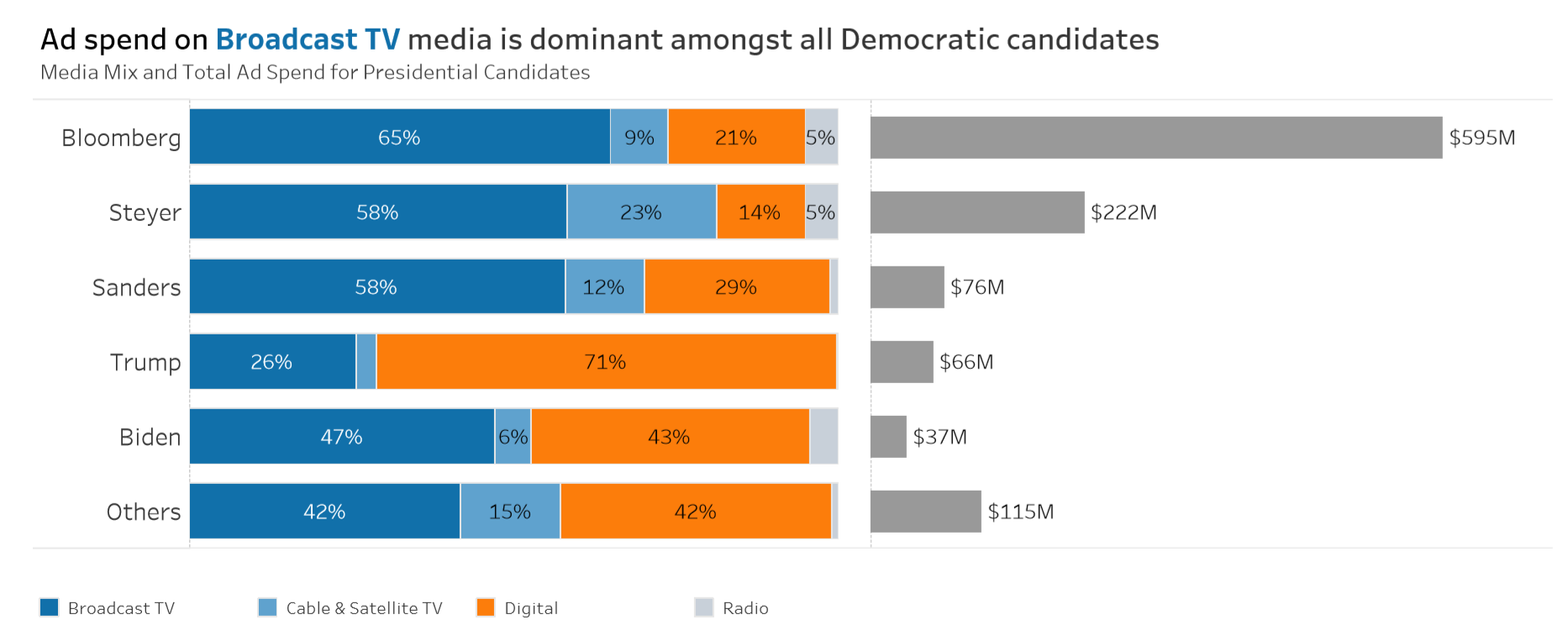

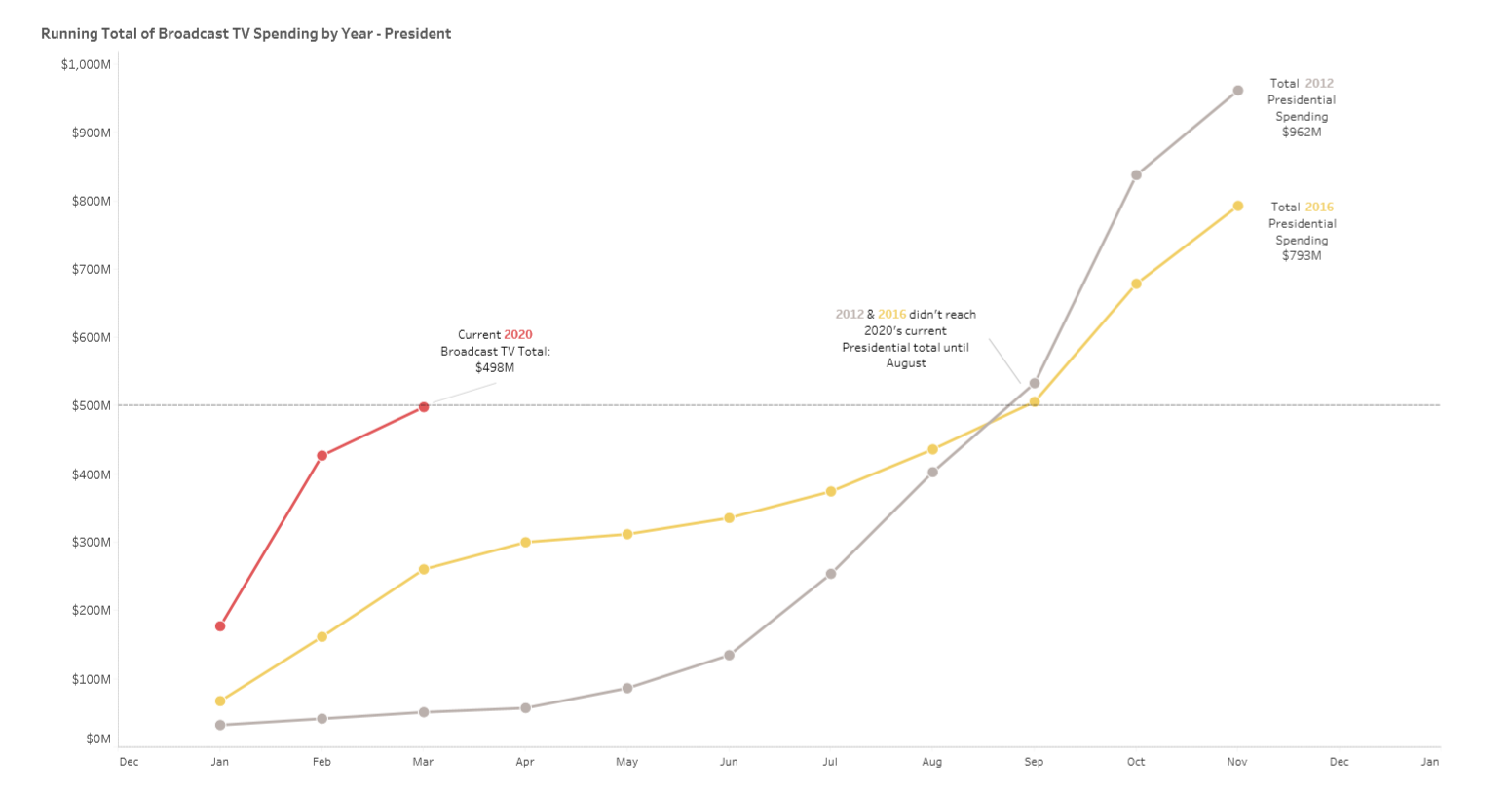

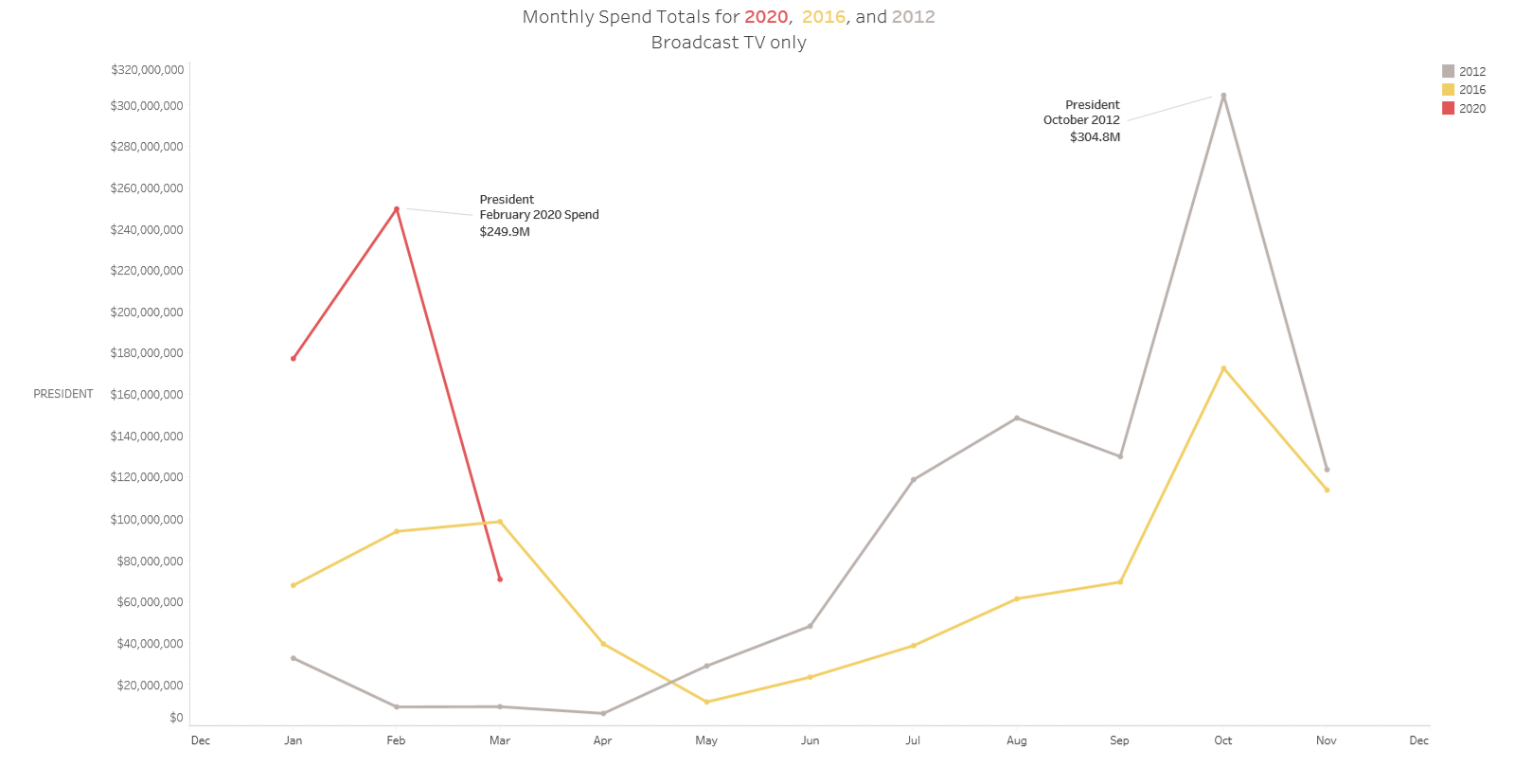

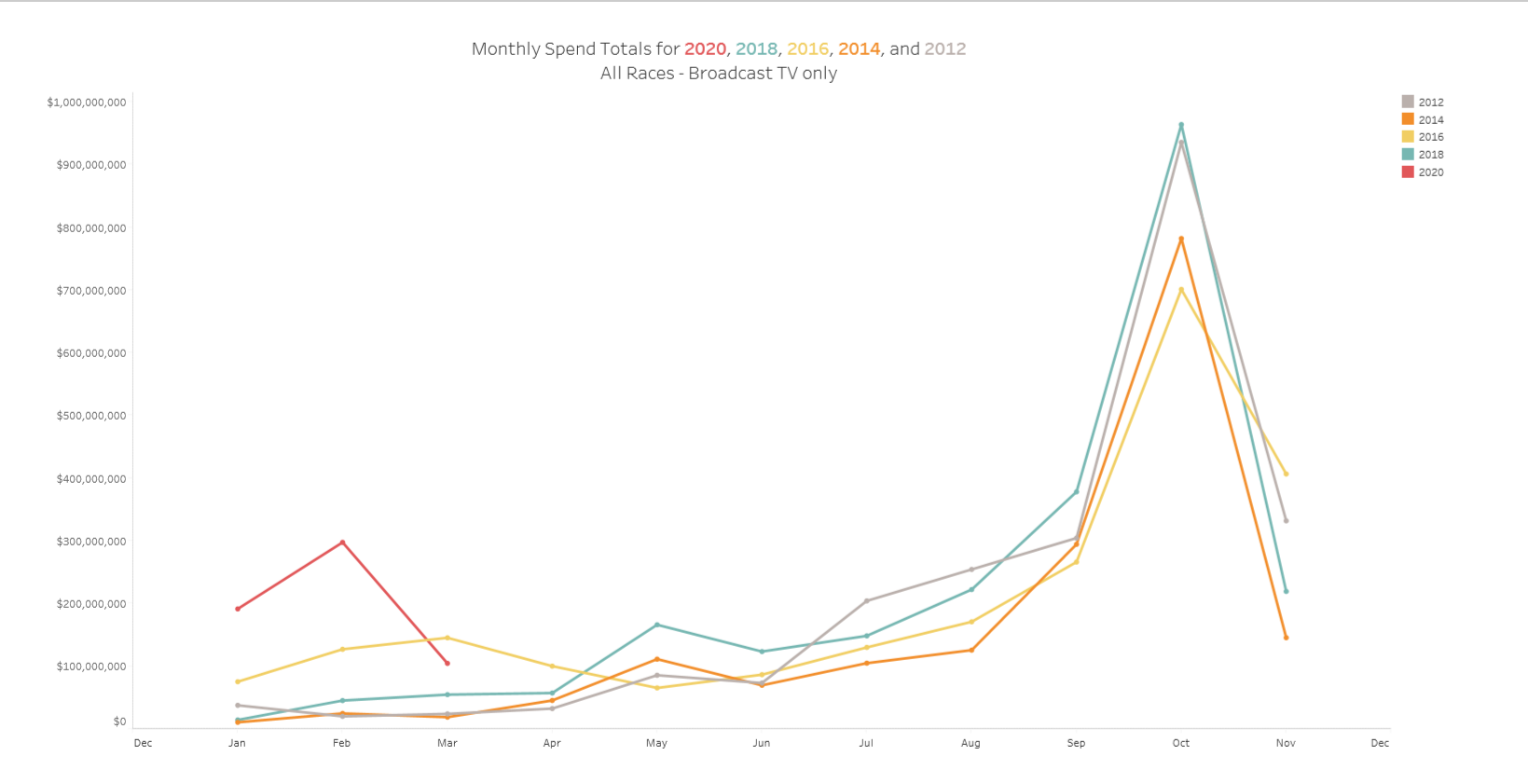

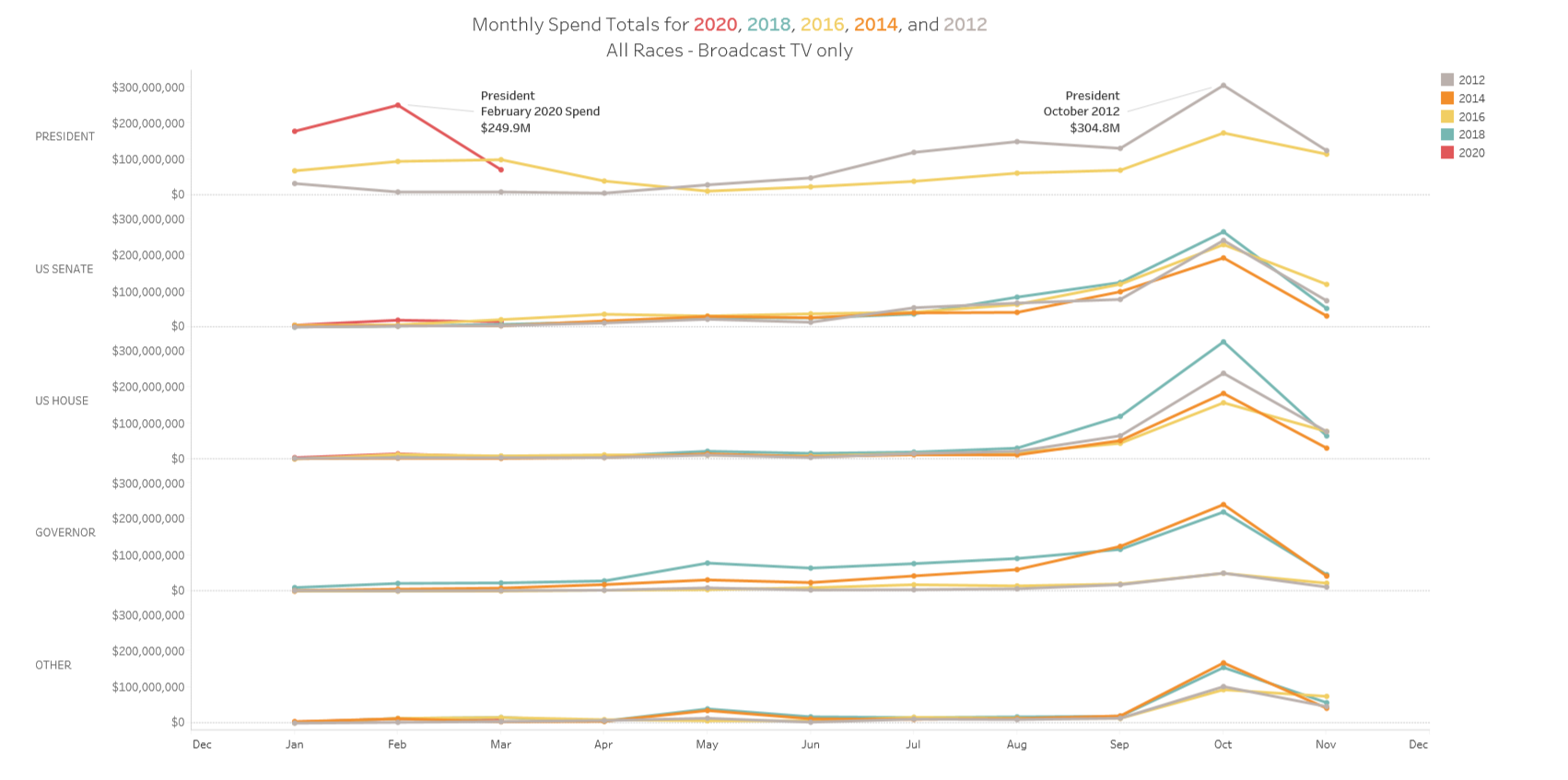

Anyone sitting around fretting over or just counting the political ads that are not running due to the unprecedented disruption wrought by COVID-19 might want to put on a mask and go for a brisk walk to clear the head of misguided obsession. Not that it’s hard to understand the chaos mindset; 2020 was an unusual year for political ad spending well before the coronavirus surfaced, due to gargantuan outlays by Democratic presidential candidate Tom Steyer and even more lavish spending by former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg. More than $700 million was spent on broadcast TV this cycle by the end of March, a milestone not hit until August of 2016, and not projected to arrive this year until around July, even in projections that skewed high when compared to years past.

However, certain patterns hold. The relative dip in 2020 spending started rather abruptly and was not due to the coronavirus, but rather to Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren neatly shivving Bloomberg in the February Democratic debate. Bloomberg’s demise may have coincided with the pandemic, but the ad drop-off that proceeded was perfectly in keeping with historical trends. Political ad spending is always at its lowest point in March, April, and May.

While some political ad buyers are looking to take advantage of rates that are likely to be low in May, June, July, and August—and they may be able to do that—it’s September, and October/November (which is essentially one “month,” given Election Day falls in the beginning of November) when we’ll begin to see the effects of pent-up demand and learn how 2020 stacks up to past election years. Historically, two thirds of all ad spending happens during that two-month timeframe, which this year coincides with the moment in which much of the country is likely to be experimenting with how to restart economic engines while setting up new norms that protect public health.

As such, for the next three months, keeping a watchful eye on fundraising, as well as imagining how the fundamentals of political advertising (total dollars as a function of money raised and the number of competitive races) and the durable facts of the current presidential contest (Democrats still want to defeat President Donald Trump) might manifest in a changed fall landscape.

First, where will the eyeballs be? Never have more Americans spent more time in front of more screens of different sizes—many of them streaming ad-free subscription content such as Netflix. How quickly that changes depends in large part on how soon sports come back, and the NFL, followed by college football, is the place to look for insight.

Second, what about that pent-up demand, a natural function of a spring/summer rate slump likely more pronounced this year? Advertising revenue is a function of units and rates, which competition from advertisers outside the political sector will likely drive up. Lots of cars will be coming off their leases over the next few months and automakers will need to advertise, not to mention there will likely be an uptick in general back-to-school advertising as companies seek to take advantage of the most-anticipated “first day of school” in American history. National advertisers may also buy more local (driving up prices) if certain areas of the country are “open” more than others.

Of course, disposable income is going to be lower, and that will not only impact household purchases but also small-dollar political donations. That said, campaigns will set out to raise according to their needs, which seem to be expanding. The curve has been consistently flat on Trump’s job approval rating over the course of his entire presidency. This fact indicates a truly competitive race, which means more states likely to be engaged (and more dollars spent) than in 2016—at least in states such as Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. As reported by Inside Elections, the fight for control of the Senate is increasingly competitive, with three races moving toward Democrats recently.

More competition means a need for higher-touch campaigns, no mean feat in a year when physical proximity is verboten. If traditional advertisers must fret about something, they could worry about the share of the bounty that will go to digital, especially because data from the primary revealed no clear trend on that score.

Steve Passwaiter is General Manager for CMAG Media Division, Kantar.