Inauguration Planning Confronts Reality of Pandemic

August 17, 2020 · 2:33 PM EDT

Every four years, on January 20th, the president-elect is sworn into office, usually among the country’s political elite sitting shoulder to shoulder and in front of a massive crowd of onlookers composed of Americans from across the nation. Since 1981, presidential inaugurations have taken place on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol, overlooking the National Mall.

But in the throes of the coronavirus pandemic, how might next year’s inauguration differ from previous iterations?

The History

The Constitution provides little guidance for inaugurations, simply mandating the president-elect take the oath of office on January 20. But since George Washington took the oath at Federal Hall in 1789 in New York City, it has been tradition for the ceremony to take place outdoors and in front of crowds, and be accompanied by varying levels of religious and military pomp and circumstance. (When January 20 falls on a Sunday, there are generally two swearings-in, one private on the 20th, one public on the 21st.)

Since 1801, nearly every regularly scheduled inauguration has taken place at the Capitol, and the celebrations have become increasingly involved. In 2008, a record 1.8 million people turned out to see Barack Obama sworn in as president; Obama’s inauguration also included 10 official balls, a concert on the Mall, and a national day of service.

In modern times, inauguration crowds fall into three tiers. The first, and smallest, is people seated at the Capitol, either on specially constructed platforms or temporary grandstands. Numbering around 2,600, this group includes incoming, outgoing, and former presidents and their families, Cabinet members, Supreme Court Justices, various dignitaries, governors, and members of Congress.

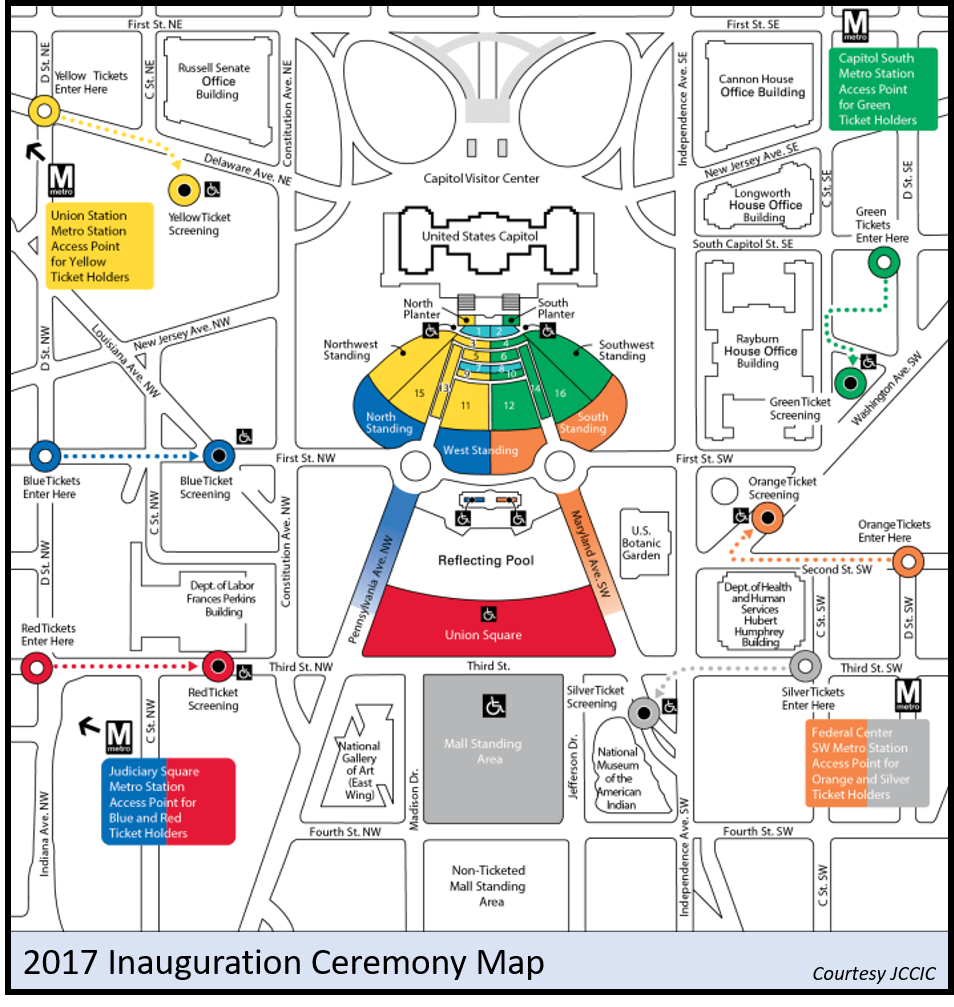

The second tier are ticket holders, 250,000-strong in 2017 and organized into color-coded viewing locations, who sit or stand in a fenced-in area in front of the Capitol.

The final tier are non-ticketed observers, who watch the proceedings from the National Mall.

The Planning

Coronavirus has already affected preparation for the event. The Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC), a six-member committee made up of the leadership of each chamber plus the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Rules Committee, usually convenes in the Spring -- in 2016 its first meeting was April 13 -- but this year it didn’t meet until June 30.

But the JCCIC is just one of two bodies responsible for planning inaugurations. The committee handles Congress’s contributions to the ceremony: the physical construction of the platform on the West Front of the Capitol, tickets for members of Congress and other VIPs, the traditional after-ceremony luncheon in the Capitol. The JCCIC’s purview extends from the Capitol Building up until 3rd Street, a restricted area open only to special ticket holders.

The other half of the equation is the Presidential Inaugural Committee (PIC), which represents the president-elect in the process. The PIC, which is not formed until after the election, handles the speakers list, all of the surrounding balls, concerts, and ancillary activities, as well as logistics for the ceremony for everything west of 3rd Street, including coordination with the National Mall and the DC local government.

A third entity, the Joint Task Force – National Capital Region, is responsible for coordinating military assets used during inaugural events.

Inauguration planning is an exercise in flexibility. Because nobody knows who the president-elect is until early November, there is only so much that can be planned in advance. Emmett Beliveau, who served as CEO of Obama’s Presidential Inaugural Committee in 2008, describes the process as “a three month sprint” beginning a few days after the election, noting that there was “zero” discussion about inaugural events within the campaign prior to Election Day.

Beliveau said in a recent interview that the “normal planning timeline for the inaugural lends itself to be responsive to the wishes of the person who wins in November,” including on issues such as health concerns. Emily Parcell, who worked as the political director for the 2009 inauguration, concurred, saying over the weekend that “one thing [the planners] will have to their advantage is a pretty good idea of the situation in the moment.”

But that doesn’t mean the organizers, particularly those at the JCCIC, can wait until November to begin thinking about the effects of coronavirus and gaming out contingencies. “There’s a flexibility there,” says Howard Gantman, who was the staff director for the JCCIC in 2008-09, “but the difference right now is the flexibility has to include different ways in which you want to handle the virus.”

Neither campaign responded to requests for comment on if and how the candidates and their advisors were approaching inauguration. But former Vice President Joe Biden himself gave a clue of his preferences in a June interview with Pittsburgh TV station KDKA, indicating that he intends to take the oath of office without wearing a mask in front of a socially distanced crowd at the Capitol.

Biden did not say if he would discourage people from assembling on the Mall to view the ceremony -- the crowd in the immediate vicinity of the Capitol is just a fraction of the total audience that usually turns out -- but his campaign has eschewed large gatherings such as rallies since the outbreak began.

Chris Lu, who was the executive director of the Obama 2008-2009 transition team and later served as Deputy Secretary of Labor, said in a recent interview that Biden “is not a person of big ego, he doesn’t need to be in front of big crowds,” and remarked that, at least so far, the former vice president has strived to create a “sharp contrast” between his own behavior and the president’s, who was famously invested in turnout at his first inauguration.

President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has been more mercurial in his approach to crowds since the pandemic began. He initially scaled back large events, only to hold a series of rallies without social distancing in late June and early July, in Phoenix, Tulsa, and Mt. Rushmore.

After his Tulsa appearance was widely panned and left several Secret Service officers ill, the president cut back on large events again, opting for “tele-rallies” instead of his signature live speeches, and pulling the plug on the in-person Republican National Convention in Jacksonville.

The Alternatives

While most inaugurations have taken place in front of large crowds outside the Capitol, there is precedent for a scaled-down ceremony, including for health and safety reasons.

In 1945, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, by then severely stricken by disease that would kill him just 82 days later, opted to conduct his fourth inauguration at the White House’s South Portico in front of a smaller crowd -- the official reason for the reduced ceremony and the cancellation of the inaugural parade was wartime austerity.

More recently, in 1985, Ronald Reagan made the last-minute decision to move his second inauguration from the West Front of the Capitol inside to the Rotunda. The reason was outside temperatures approaching 0 degrees and a windchill of 25 degrees below zero.

Instead of 140,000 ticket-holders, Reagan was sworn in before just a few hundred select dignitaries. The parade was cancelled as well, sparking frustration from the many thousands who had traveled to D.C. to participate. “It’s a tragedy,” noted American Conservative Union director Jake Hansen at the time, “but you can’t get mad at God.”

The 1985 event provides precedent for a small ceremony, said Lu, the former Obama official. Belvieau similarly agrees that even decades later, at a time when these events can attract millions of visitors instead of hundreds of thousands, “it’s very possible to hold a dramatically scaled-down inauguration.”

But while the inaugural committees can restrict the number of tickets distributed, there’s no system in place to stop people from observing the ceremony from the unrestricted areas. Asks Gantman, “what do you say to the people who want to come to the National Mall?”

Even if the president-elect discourages people from attending in an attempt to avoid the sardines-esque packing of the Mall seen in previous inaugurations, people may attend regardless. One former inaugural staffer noted that the PIC decides if and where to place jumbotrons, bike racks, and other amenities that make the Mall experience more pleasant, and that if the president-elect wanted to discourage crowds he could limit those amenities.

But perhaps the best way to comply with potential social distancing rules would be to create a viable, attractive alternative to physically showing up on the Mall, one that still allows Americans to participate in and celebrate the democratic process.

Lu pointed to this week’s Democratic National Convention (to which he is a superdelegate), conducted virtually from dozens of locations around the country, as a potential model for the 2021 inauguration.

When asked how he would approach an inauguration done under social distancing guidelines, Beliveau also cited the DNC as a model, as well as decentralized programs he helped organize for the 2009 inauguration such as a national day of service on MLK Jr. Day, and a “Neighborhood Ball” where small gatherings across the country were virtually streamed into a free event held by the Obamas in D.C.

Jean Bordewich, staff director for the JCCIC in 2012-13, offered another source of inspiration: next year’s Sundance Film Festival. Writing in The Hill last month, Bordewich explained that the 2021 inauguration could resemble the festival, which will take place “simultaneously as smaller live events in Park City, at cinemas in at least 20 other cities, and online,” and that the ceremony’s planners should take advantage of the “fresh waves of creativity among performing artists and their audiences” brought forth by the pandemic.

Parcell, the 2009 political director, is optimistic about the potential for inaugural innovation. “It could be a very interesting planning opportunity for the incoming president and inaugural committee to think about the story you really want to tell,” she says, “and the medium by which you’re telling that story, if it becomes primarily video, it does in a way open up the accessibility of the inaugural to every single person in this country and around the world with a video link, which could be really intriguing.”

Another issue raised by several former inauguration staffers was the effect of a large ceremony on the city. The possibility of tens or hundreds of thousands of visitors from all around the country converging on one spot could pose a significant health risk, not just as people pack the National Mall but also in the Metro cars and city buses that would be inundated with travelers, the hospitality services that would have to scale up to meet increased demand, and the close quarters of the planes and chartered coach buses that ferry people from hundreds of miles away to DC.

One former staffer also questioned whether the intensive security requirements of the ceremony -- with measures such as street closures leading to traffic delays -- could hamper the city’s emergency response abilities during the midst of the pandemic.

For now, the JCCIC is planning for as close to normal an event as possible, and is on track to conduct the traditional First Nail ceremony in mid-September as it has in years past. The committee continues to monitor the health situation, working closely with the Attending Physician of the US Congress Brian Monahan, and with input from the CDC.

Coronavirus has introduced uncertainty into every facet of American life, including planning for the next inauguration. But because the process is already so confined to the few months between Election Day and Inauguration Day, whoever the president-elect is will be able to plan the event informed by the latest data, from late November and early December.

We won’t know until we get there. Biden may have put it best in Pittsburgh: “We don’t know what it’s going to be like on January 20th, 2021.”

Gantman, the former JCCIC staff director, is more blunt. “Unless the scenario changes in terms of coronavirus,” he says, “it’s hard to imagine that this would be able to happen like it always has."